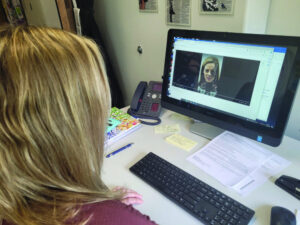

Kim Lyng, liberal arts professor and program coordinator and Performing Arts and Communication Department Chair, looks at an AI version of herself on the computer in her office in the Spurk building. Lyng recently debated this “AI Kim” on the impact of artificial intelligence on educatioin in an event organized by CIS Professor Devan Walton. Photo by Editor-in-Chief Kim Zappala

AI promises to revolutionize the way we do everything, including coursework, but NECC faculty and some students have concerns about this future.

With a new semester underway, and new developments in generative AI technology made public at a regular pace, these concerns are renewed around our campus.

Professor Devan Walton, who teaches computer and information science courses here at NECC, says that other faculty reach out to him regularly.

“Probably twenty distinct emails, and double that in-person. They express a lot of anxiety about AI, they’re anxious about the future. This could be the end of everything. So, I ground them in reality.”

What is that reality?

Many of us are familiar with programs like ChatGPT, a generative text model that can generate text based on written prompts you feed it. Students and teachers alike worry about its ability to write essays. And these fears aren’t without merit, Walton says. “Depending on the model, you can make work indistinguishable from a top-mark student.”

The only issue is when the AI experiences what experts call “hallucinations,” where the AI generates content that is demonstrably false.

But advances in the programming and training of these models makes them more and more accurate with each iteration.

“More sophisticated, paid models, the rate that it creates false content is much lower, except in math,” Walton notes

Educators aren’t alone in having concerns about AI.

Olimar Gonzalez is a Nursing major at NECC, who says that using AI to write a paper is plagiarism.

But it’s also become more prevalent in everyday life.

“When I did a Muhammad Ali essay, I looked up stuff on Google, and it started to type up an essay.” She also said that she had an English Composition professor that made his students turn in all their papers on Turnitin to check all their written work to make sure it wasn’t written by AI.

Lauren Iannitelli is a Nursing major that works at Mass General, and says that she has used ChatGPT to study. Even then, though, she’s wary of its uses. “I feel it could turn on us in a way. I like the idea, but taking over jobs, I don’t think it should do that” Iannitelli says. “They advertise AI at my hospital. What if we can’t afford it, and we’re left without people that know what to do?”

Gonzalez agrees. She says “Now there’s a machine that does the chest compressions. And there’s the EMT guy, waiting for the machine to do it instead of doing it himself.”

It’s important to note the benefits AI tools can have in the classroom, professor Walton says. “It can identify weaknesses in an activity or curriculum” he says. “You can give ChaptGPT an assignment, ask it to make it more accessible, and it can answer that.”

As technology advances, what can we as a community do to address it? Walton believes that AI tools and their use will become an inevitability. “I think as it becomes more accessible, it’ll become the norm to expect students to collaborate with AI. AI collaboration will expand the types of problems we can address in the classroom. This AI future might not be great, might not be bad, it’s hard to say. When people say it’s bad, I understand that. But I also hope for a future where students can use it to tackle larger problems, and lead to a brighter future.”

So what does he recommend? “One thing I recommend people do is try using these tools. Most people with a lot of anxiety haven’t used them. Having used them and understanding their limits and capabilities can help.”